Kicking away the dirt hiding Roman history and finding what lies beneath...have we got the age of Rome all wrong?

Thursday 28 February 2013

Made in Ancient China

In 78AD Pliny the Elder wrote, "Man now quarries mountains for marble, seeks clothes from China, pearls from the depths of the sea and emeralds from the depths of the earth." I guess some things never change - 1934 years later and the Global Economy is just as the Romans left it. We're still digging up mountains and still importing clothes from China. The more we think we've changed the world, the more we copy the past. Economies come and go, but when you peel back the layers you can see they're all pretty much the same. We find something to sell and someone else sends us something to buy. I wonder if the Romans had trouble finding Chinese made XXL shirts too? For more on Roman trade - check out 'Mischance and Happenstance' - live on Amazon now

Wednesday 27 February 2013

Ancient Plastic surgery

In this age of beauty before everything - where the surgeon's scalpel is seen as a fashion accessory - it would be easy to assume this was the modern world's domain alone...but, alas - it's not that new. We have been fighting age for a very long time. Nose jobs, breast reductions, face lifts - all things available to the Romans who could afford it. For those who hadn't been looking after their teeth, there were bridges and crowns to keep that winning smile. And for those a little more dubious about going under the knife, there was a cosmetic industry not matched until the great name brands of the last century. So next time you think about new look, just remember, it's getting pretty old. For more Roman History - check out 'A Body of Doubt' - live on Amazon now.

Tuesday 26 February 2013

A concrete post

Since the invention - or should we say the reinvention - of 'Portland Cement' in the 1830s, we bastions of the industrial and computer ages have made monumental buildings a matter of poured concrete. Most structures we drive on or live and work in would not be possible without the wonders of 'modern concrete'. It can be pumped hundreds of metres into the air and set hundreds of metres under the sea. It has made the twentieth and twenty-first centuries possible. No small thing for a mortar invented for canal construction.

But in essence, all we've done is reinvigorate a construction material discovered even before the Romans conquered most of the 'known' world. The Carthaginians were building multi-storey concrete buildings prior to 146 BC, and the Romans almost certainly adopted this Punic technology to build eight-storey tower blocks in Rome and other major cities...and some of these are still standing. Meanwhile the Pantheon, the world's largest uninterrupted enclosed space for 1900-years, offers a salute to the engineering we have only just rekindled. However Roman cities were just the beginning. Concrete built the roads and the aqueducts that fed an empire, and hundreds of thousands of tonnes of Roman concrete was poured into the sea. The sea you ask? Yes, perhaps the greatest achievement of all. Vast artificial harbours designed in a time before modern diving equipment, let alone cement mixing machines. King Herod built the artificial Caesarea Harbour in 20 BC, constructing it entirely from concrete bulwarks sunk in place...and still in place. North of Naples, Pliny the Elder's naval base used a similar technique, although in this case, parts of the harbour wall sink over one hundred feet below the sea's surface. How this was achieved and the how the sea floor was prepared raises a lot of questions, many of which we will have to look at in the future - such as - could any of this have been done without the use of stored or piped air for divers? The fact the Romans used concrete so freely must mean they used other accompanying technologies we remain oblivious to. Perhaps there's no concrete answer - but for more on Roman diving technology - check out 'A Body of Doubt' - live on Amazon now.

Monday 25 February 2013

Diamonds are a Roman's best friend

If you think diamond edged cutting tools are something we thought of in the 1950s, then Pliny the Elder can tell you the Romans knew all about 'Industrial Diamonds'. In 78AD he describes how the shards left over from 'breaking' a diamond were used by engravers - who inserted the slivers into their iron cutting tools because, "they cut into the hardest surfaces with little effort." Waste not want not. Even at that time diamonds were considered the world's most valuable gemstone, so this would have been a brave decision to turn such a rare stone into a stone cutter.

For more Roman history - check out 'A Body of Doubt' - live on Amazon

Sunday 24 February 2013

Gladiators - less swords more sandals

Gladiator was on TV again last night - and while I don't want to knock this Sword and Sandal Blockbuster and its historical shortcomings - like Commodus dying about twelve years too early; or using the wrong artillery pieces in the opening battle scene - this movie remains a prime example of how the Gladiator myth has been perpetuated. Sure, this was sport and spectacle at its most gruesome - men and women most certainly fought to the death or were maimed terribly in the process. The question is, was this the daily fare served to the hoards with hot nuts, as poor, hapless slaves died at the drop of a thumb? The answer is no. This was a highly organised and professional sport, with millions invested by individuals or consortiums and millions more passing between punters and bookmakers. The similarities between Roman weekend sport and our modern forms is stark. Yes, some of the gladiators were slaves. But many were volunteers - slaves, freedmen and citizens seeking the same glory and money as today's footballers, boxers or racing car drivers. And slave or not, the financial rewards for entering the arena were probably justification enough for the risk. Gladiators usually retired multi-millionaires and the toast of their respective cities.

Retired, you say? How did they survive long enough for that? Well, put quite simply, most fights were not to the death. In fact, I suspect gladiators often performed more like American pro-wrestlers rather than in the cut and thrust action we see in the movies. Think about it...the owner of a gladiator team would have spent the modern day equivalent of $1.25-million on each fighter to buy and train. Like a prized race horse or racing car driver, the team owner would know there was a certain danger in each bout, but he wouldn't be in the business if he lost a fortune everyday...or even every year. The simple fact is that the sheer cost of each gladiator would have made the business model unworkable if the expectation of death was the primary focus. And as if to enforce this fact, a gladiator cemetery recently found in Turkey - beside an arena that remained in use for two hundred years - had only thirty bodies interred in it. Hardly indicative of mass killings every public holiday. So the next time you watch Gladiator or Spartacus, just remember these heroic victims of circumstance were worth far more to their promoters and owners alive than we give this terrible sport credit.

For more Roman history - check out 'Mischance and Happenstance' - live on Amazon now

Saturday 23 February 2013

The World's first oil shock

Oil has caused all sorts of troubles for us...Japan bombed Pearl Harbour because if it and Germany invaded Russia because of it. The Gulf War...one and two? Oil is the grease of this modern world, take it away, and everything stops. So far this hasn't happened - but if you a want a lesson in what would happen if it did, then we need only look to the fall of the Roman Empire - the First Millennium's great oil shock. Of course, it wasn't sweet light crude back then, it was olive...but don't think for a moment the Roman world collapsed because the demand for salad dressings stopped. Just like modern crude, olive oil kept the lights on, it kept the wheels of industry and trade turning and every last person used it for skin lotions and bathing...just as the petrochemical plants provide for us today. Now just imagine what would happen if one day you went to the supermarket and found every single product you relied on wasn't there...and then you went home and sat in the dark - all because your government couldn't stop a bunch of Visigoths and Vandals cutting off the oil supplies from France, Spain and North Africa. One by one the provinces drifted away from the core, siding with the northern barbarians just so the lights would come on at night again. Now, perhaps this sounds all too simple, but think about...put yourself in their position. If your government stopped providing for you - but some else offered to help instead...what would you do to keep the lights on?

For more on Roman history check out 'A Body of Doubt' - live on Amazon now

Thursday 21 February 2013

What did the Arvernians look like?

We've covered the stylistic appearances of the Celtic Gauls before, so this answer is going to be more about the physical face the Arvernian people presented to the ancient world - and to attempt to describe the average inhabitant of central Gaul. For starters, we know the Romans and Arverni shared the same common ancestors, so many of the faces we see in Republican-era Roman busts will reflect in some way what an Arvernian looked like. Of course, by the 3rd-century BC the 'Celtic' Romans were mixing with Etrurians (who originated from Turkey) and pre-Celtic Italian populations, so tendencies towards darker hair and skin would have been changing the 'look' of the Republican Roman from that of Romulus and Remus. However this was most likely not happening in Celtic Gaul, where the population probably remained largely homogeneous - with some exceptions on the Mediterranean peripheries where Punic, Greek, Etrurian and later Roman colonies existed or in the borderlands of the Belgic Gauls whose general appearance may actually survive in the modern Flemish and Dutch populations.

So having said all that, here's my best guess of an Arvernian. With a higher protein diet than Romans, Arvernian men and women were generally taller - many would have stood at least 6'0", with average heights of men and women being somewhere around or above 5'6" whereas the Roman average was closer to 5'4" and Roman men rarely reached 6'0". The Arverni were not heavily built like the Belgics and Germans, instead they tended towards a lanky Scandinavian-like body shape - perhaps with a more rounded face, high cheekbones and eyes closer set as a result.

Their skin has been described as milky white so their complexion would be generally described as fair, although blonde hair and blue eyes may not have been as common as you might think. Even today the population of central France tends towards brown to black hair, I think it's a reasonable assumption the Arverni did too, with brown eyes much more common, with red hair and freckled skin appearing occasionally (the latter appears far more common in post-Viking cultures than the pre-Viking populations of western Europe). What may have made an Arvernian distinctive (or at least some of them) was their nose. The coins of Vercingetorix exhibit a long straight nose diving downwards from the forehead, a family trait perhaps, but a shape that can still be seen in modern post-Celtic cultures in Britain and Ireland.

Okay, so is it possible to still see the 'Arvernian' look in popular culture? Off the top of my head I can think of two actors who offer a modern day resemblance to the people of Celtic Gaul. Liam Neeson and Tamsin Greig both share many of the traits that would have been common to the Arverni - in fact Tamsin was even born in a part of England where Arverni refugees from the 'Great Rebellion' most likely settled - this is of course most likely coincidence, but an interesting one nonetheless. Lets hope next time a movie is made about Vercingetorix they both get starring roles.

For more Arvernian history check out 'The Hitherto Unknown' - live on Amazon now

Wednesday 20 February 2013

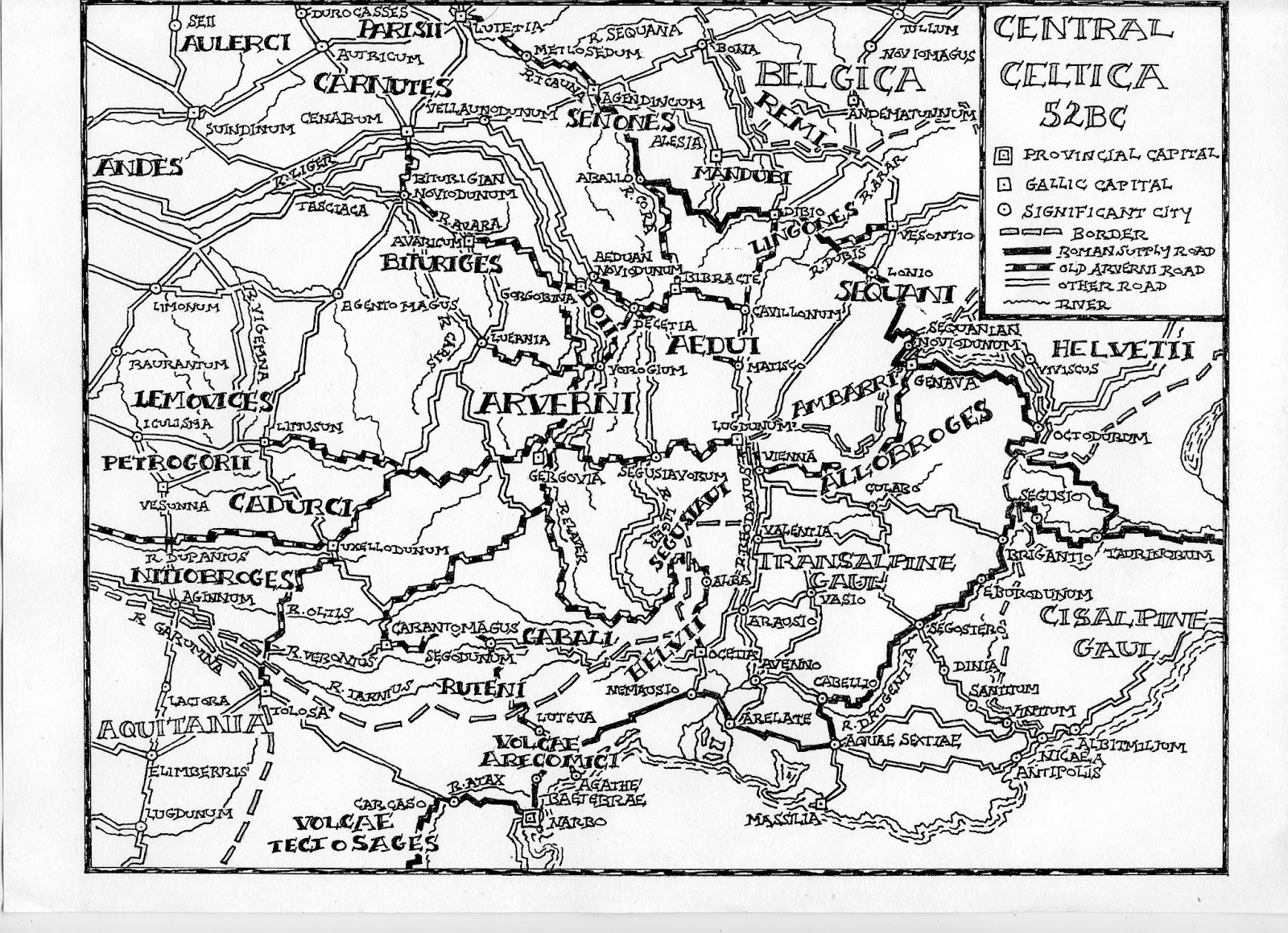

The Pan-Gallic Arverni Kingdom

As is usual with Gallic history, if the Greeks or Romans didn't write about it, we pretty much don't know what happened in Gaul other than what 2000-year old ruins can tell us. Add to this a few preconceptions the Romans in particular have provided modern scholars and we can have a lot of trouble nailing down exactly what was happening in central or 'Celtic' Gaul before 126 BC. At some point during the 4th or early 3rd centuries BC the Arverni began doing their own empire building - again roughly corresponding with Rome's rise in Italy. The neighbouring tribal states of the Cadurci, Eleuteti, Gabali and Vellavii - mostly to the southwest or across the Central Massif, were folded into a growing Arvernian Kingdom. In doing so, this probably made the Arverni third most powerful 'nation' state west of Greece - behind Rome and Carthage. And the growth didn't stop there. By the end of the 3rd-century BC - around the time Hannibal was campaigning in Italy, the Arvernian Kingdom had expanded eastwards to swallow up the vital trading routes along the Rhone and Saone valleys, placing the powerful tribal states of the Allobroges and Aedui under Arvernian rule. At this point the Arvernian Kingdom stretched across all of southern France to the Alps, and almost as far north as Orleans, Paris and the borders of Belgic Gaul. At this point, the Arverni probably controlled more lands and people than Rome or Carthage.

So how did they do it? Brute strength - like Rome - would be the easy answer, however luck and circumstance can't be ignored. As I've already mentioned, they controlled most of the land routes between Carthaginian Spain and Gaul for at least three centuries. By the 3rd-century BC, they controlled all of the land routes, not to mention the Rhone and any access to the Alps. Hannibal's journey across Gaul was almost entirely through the Arvernian Kingdom, and much of his Gallic troops and resources were provided tribes controlled by the Arverni. What we can take from this, is a strong alliance existed between the Arverni and the Carthage during the Second Punic war, something that has been understated in the past with most historians looking upon Hannibal's passage of Gaul as an event independent of Gallic approval. And on the back of this alliance, with Rome busy fighting off Hannibal and warriors from parts of the Arvernian Kingdom , the Arverni reach the height of their powers and wealth...coincidence? With Carthage behind them, the Arverni were too powerful to be stopped by Rome. But what would happen when Carthage vanished? We'll see tomorrow.

For more Arvernian history check out 'The Hitherto Unknown' - live on Amazon now

Tuesday 19 February 2013

Who were the Arverni?

Parallels are frequently made between the rise of Carthage and Rome - they were founded at roughly the same time and used different economic models to become the preeminent Mediterranean superpowers of the 3rd and 2nd-century. Ultimately we got to see the Roman model of 'world domination' by military might and financial trade trumped 'world domination' by controlling mercantile trade. However, often forgotten in this scenario is another western tribal state with again many parallels and connections to Rome and Carthage. This is the regional - rather than city - state of the Arverni.

Just as the Romans were arriving in Italy, the Arvernians arrived in central France around 700BC. The Romans and Arvernians both originated from parts of modern day Austria and these two Celtic cultures both replaced existing populations where they settled. In the area around Clermont-Ferrand the Arvernians displaced a much older European culture that was forced westwards to the Atlantic coast to become the Aquitani - who have since become the linguistically unique Basques. The Arvernians then established the tribal hilltop capital - Gergovia - but unlike the Romans who settled for a single city, the Arvernians took control of a vast area of central Gaul west of the Loire River, south to and over the Central Massif and west into the Dordogne and Lot Valleys. In doing so they held almost all of the richest river valley's across western Gaul giving them prime agricultural ground and an ability to trade directly into the Atlantic.

The fact their trade routes were westward facing rather than eastward gives some big hints that as the Mediterranean basin power bases moved from Greece and Egypt to North Africa, Italy and Spain, early Arverni wealth was almost certainly derived from the British metal trade moving cross-country into Gaul or southeast to Etruria. However, as Carthage became more heavily involved in the Atlantic sea trade during the 5th and 4th-centuries it would seem the Arverni were in a perfect position to tax and profit from those growing Atlantic trade routes crossing Gaul, and new overland corridors to Carthaginian Spain. In other words, while later Arverni history was intrinsically shaped by Rome, the formative centuries leading to the creation of a Pan-Gallic Arvernian kingdom was most likely driven by Carthage.

What happened next? Well, that tomorrow's post.

For more Arvernian history - check out 'The Hitherto Unknown' - live on Amazon now

Sunday 17 February 2013

Got a headache?

You get a headache you take a pill, right? Easy. I bet you don't spend a lot of time thinking how someone coped before the multinational pharmaceuticals came along, but if you did I suppose self-medicating with medicinal brandy or something similar comes to mind. After all, all these modern painkillers we take for granted are just something that came along in the last few decades...and yes, some of them have. But not all of them.

Opium poppies have been farmed almost since the beginning of cultivation...and until the 19th-century opium derivatives had been the go-to for pain relief across the Europe and Asia. For the Romans, poppy syrup was being taken in tablet form, which meant a big dose of all the opiate alkaloids - particularly morphine - with every pill. In the 1st-century AD, Pliny notes several leading medical authorities already campaigning against the use of raw opium, sighting blindness and fatal comas as a very real danger. So what was the alternative? It might surprise you, but it's probably something you've taken and might even have in your medicine cabinet even now. What is it? Codeine - second to morphine as the most common alkaloid found in opium. Pliny describes the drug as 'well-known' but unfortunately doesn't elaborate on its production and refining from raw opium - presuming, I suppose - that most of his readers knew what he was talking about. What is interesting is that Romans were buying Codeine tablets in the 1st-century AD despite the alkaloid only being 'rediscovered' in 1832. Obviously Roman chemists were just as sophisticated as their 19th-century counterparts - and face it, if you've ever had a headache, you'd certainly be wanting to buy something to get rid of it - the Romans understood supply and demand.

Check out more Roman history with 'A Body of Doubt' - available from Amazon now

Thursday 14 February 2013

The Animal Kingdom

If you've stood trackside and felt the thunder of a dozen horses racing past you, then just imagine what it was like in 52BC. Caesar's cavalry numbered some three thousand and Vercingetorix had fifteen thousand horses escorting his main infantry force. In the Battle of Dibio, the biggest of the horse battles, there may have been up to eighteen thousand horses spread across the plains now filled by the city of Dijon. Just imagine the sound, the sensation and the dust. But beyond the vast statistics of this cavalry battle...what about the logistics? Feeding and watering tens of thousands of horses everyday, winter or summer - and it wasn't just the war horses either. Caesar's army also had six thousand mules, the Gauls had at least twice that number of pack animals. Each of these wore cow bells so their attendants could find them in the dark - which is probably the sound missing from movies or documentaries showing ancient armies on the march. Over the trudging hobnailed boots would have been the ever presenting ringing of thousands of bells. And almost certainly, every ancient soldier's memory of sleeping in camp was the tolling of those bells out there, somewhere in the dark, a constant every night he was a soldier.

Check out the latest release 'A Body of Doubt' - the ultimate Roman crime-thriller - live on Amazon now

Wednesday 13 February 2013

Happy Valentine's Day

Well, it's already Valentines Day somewhere in the world, so it's probably a good time to take a look at the story of Valentine. That's the first problem, there was more than one Valentinus (a name that means strong and healthy), in fact there are a number of Christian Martyrs bearing this name. Valentine of Terni became the local bishop in 197AD and was executed during the reign of Aurelius. The priest, Valentine of Rome, was martyred around 269AD. Both were buried alongside the Via Flaminia highway, and the skull of the latter can now be seen in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Rome.

Valentine of Rome is the most likely candidate for the Saint Valentines story - a story which revolves around a Christian priest illegally marrying soldiers after an Imperial decree banned marriage - with the typical martyrdom results. Of course, the question is, would Valentine have been executed for marrying members of his church? First of all, this supposed ban marriages during 269AD. Right from the beginning of the professional Roman legion during the last decade of the 2nd-century BC, soldiers were not allowed to marry during the course of their 16 to 20 years of service, a situation that was still standing in 269AD when Valentine came along. A new and total ban on marriages across the Empire was at the very least superfluous, and the long standing military edict is the most likely origin for the the story.

Of course, then you've got to define a marriage - obviously it would have to be recognised by the state and since the Christianity wasn't sanctioned by the Roman state in 269AD, it seems pretty unlikely a 'Christian' marriage would have been recognised as an official marriage. As such, from a Roman legal point of view, Valentine may have been going through the motions of marriage, but the couples were not actually married - thus no law was broken. And no matter how crazy Christian stories like to paint the extremes of Roman law enforcement, if it's not illegal then Valentine wasn't going to end up in a lion's cage.

So was Valentine executed? Well, he may have been, another part of the story says upon meeting Claudius the Second to plead his case, he tried to convert the Emperor - a situation that led to a summary execution. Technically, Christians weren't being executed for being Christians in 269AD, they were being executed for treason. The 250AD "For the safety of the Empire" edict of Decius required citizens to conduct sacrificial offerings before local magistrates to receive a 'certificate of loyalty to the ancestral gods' - in other words to hold a certified oath of loyalty to the Empire. Anyone not holding this certificate could be construed as an enemy of the Empire...thus a sticky end. If Valentine was executed, this is the most likely reason for his martyrdom.

As for how Valentines Day got to be so romantic? Well, you'd have to ask Chaucer that, he popularised the day in 1382 when he wrote "For this was on Saint Valentine's Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate."

Check out "A Body of Doubt" - the ultimate Roman crime-thriller - live on Amazon now

Tuesday 12 February 2013

Body Image

Just in case you think the last decade's obsession with removing body hair from all of its traditional nooks and crannies is something new...well, the bad news is it's just an age-old trade rehashed by 'Sex in the City'. The truth is, mass hair removal had become popular by the end of the Roman Republic in the 1st-century BC. Just as today, waxing was standard fare, however most bath-houses (the Roman version of a beauty clinic) also employed the infamous 'Depilator'. Armed with a pair of tweezers and a will to inflict pain on all genders, these were the true artists of hair removal, and were paid handsomely for the agony they could inflict. Seneca is quoted as saying, "The only thing louder than the depilators hawking their trade were the screams of their victims." Just goes to show, body image, and any amount of suffering for it, hasn't changed all that much.

Check out the novel 'Vagabond' on Amazon - a runaway priestess in Gaul

Check out my latest release on Amazon 'A Body of Doubt' - the ultimate Roman crime-thriller

Monday 11 February 2013

The Gallic Wars - what if?

Since the topic of Gaul is getting a bit of a run at the moment, it might be time to consider a snapshot of the results and 'what ifs' of the Gallic Conquest. What has to be taken from this war is that at any moment it could have changed our world history - if Julius Caesar and his legions had been obliterated during the campaign then we should start imagining the 21st-century without our current calendar. Imagine a present day without the Latin Alphabet. Imagine a world where Christianity and Islam had no empire or imperial legacy to spread them. This all could have happened if Caesar had failed. But then, consider what happened because he didn't. In 58BC there were six million Gauls living in dozens of tribal states across modern France, Belgium and the Netherlands. By the end of 52BC Gaul had become a single nation under one King - however one million were dead and another million Gauls were enslaved. Modern, heavily armed armies of up to 250,000 men had waged total war against each other - bringing a scale of destruction to western Europe that was never really equalled until Napoleon or even World War One. And this was all because of Julius Caesar's need to evade his political enemies in Rome. Love his legacy or hate it...we are living in a world that Caesar gave us, which, for those victims of Gaul was quite the bitter pill to swallow. What might have been the alternative history the Gauls could have given us? I guess we'll never know.

Check out the novel 'Vagabond' on Amazon - a runaway priestess in Gaul

Sunday 10 February 2013

So what have the Gauls ever done for us?

You might think this a pretty bizarre question, right? I mean the Gauls were culturally assimilated into the Roman Empire 2000-years ago...there can't be anything left of their lifestyle that still impacts on us? Well, be ready to be surprised. Despite the impact of Rome on our Western World, we act, and even dress a lot more like Gauls. How so? There's trousers of course. When the Romans were running around in overgrown Ts, the Gauls were wearing the ancient take on Levis. It wasn't the Roman tunic that reached the modern world, it was the Gallic trouser.

Okay, so that's one thing. Anything else? Sure is - here's another. Most of us don't bathe in aromatic bath oils and scape ourselves down with stridgels. That habit died out in the west centuries ago. Instead we like to use a lump of fat filled with alkaloid salts - a habit polite Roman society found appalling yet a huge business these days. That's soap for you, another invention by the Gauls and something we take for granted - even their word 'sapo' has more or less survived to this day as 'soap'.

Then there's what you had for breakfast? Did you spread any butter on your toast? Butter was brought to prominence in Europe by the Gauls. The Romans only used it in poultices to heal wounds, it was the Gauls who spread it on their bread. Additionally, the Gauls consumed far more meat than the Romans, including beef, which the was unpopular outside of Gaul. The Western diet of big meat dishes has more to do with Europe's Gallic history than the Mediterranean cultures. And then there's how we eat. Most of us don't lounge about on the floor or sofas like the ancient Mediterraneans, sitting at a table on chairs is a very Gallic thing to do, and something that survived 500-years of Roman slouching.

So the next time you wash your hands with soap, sit at a table to eat or spread butter on you bread, then think of the Gauls - they're more a part of you than the Romans ever were...strange, but true.

Check out the novel 'Vagabond' on Amazon - a runaway priestess in Gaul

Check out the novel 'Vagabond' on Amazon - a runaway priestess in Gaul Check out the novel 'A Body of Doubt' - the ultimate Roman crime-thriller

Thursday 7 February 2013

Stand off warfare - Roman style

|

| A loaded three-span Scorpion |

The one thing that made the Roman Army stand out from its 1st-century BC peers was artillery. Here was the first massed use of torsion weapons so advanced that their range and accuracy would not be matched by blackpowder cannons until the 18th-century, and with firing rates American Civil War Generals could have only dreamt of. Think about it, in 52BC Julius Caesar's ten legions mustered 100 ballistae, each capable of delivering a 15lb stone or lead projectile 500-yards every 30 seconds - that's a thousand aimed stones slicing through walls or battlelines every five minutes. Then there were the 600 three-span scorpions - each firing a three-foot long dart every 20 seconds. Any charging horse or man at 600-yards was easy pickings, with these light, pivoted point-and-shoot weapons.

You would imagine those barbarian hoards from Gaul were up against it from the start, right? After all, Caesar doesn't make mention of these brigands having anything more than a nasty attitude. But there are a few hints he leaves us that suggests the modern Gauls weren't as backward as he'd like his readers to believe. For one, he describes the walls of the fortified Gallic cities in some detail, suggesting they had been designed specifically to repel siege weapons. The trouble is these cities had been standing for at least a century before the first Roman military incursion in 58BC...so it wasn't Roman siege weapons they were built for. Nope, the only threat to one Gallic walled city was from another. And in two other passages he describes missiles being thrown into his fortified camps - what kind of missiles, he doesn't say, but the fact that both times the event caused great consternation among his men suggests it was more than a local tribesman lobbing pebbles.

This is further borne out with the great siege works thrown up around Gergovia and Alesia by the Romans. Caesar completed ditches six hundred yards from his own fortifications in both cases. Perhaps it was just to slow the Gallic advance, but I suspect it was more than that. These ditches were at the outer limits of scorpion range...but you have to wonder, whose scorpions? Certainly, a deep ditch would make it difficult to wheel heavy artillery pieces into range of the Roman walls.

|

| A Scorpion and Onager side by side...they don't share much in common do they. |

The thing is the Gauls didn't live in a vacuum. They didn't want to die pointlessly. And many had seen action as cavalrymen and tribal auxiliaries in Caesar's army before 52BC. They knew what Roman artillery could do...and here's where I'll go out on limb...I think they already knew what their own artillery could do. They were using siege weapons long before Caesar showed up, and if they hadn't copied the Greek weapons the Romans used, they may have designed their own. We even have good evidence of this - because there is one missile throwing machine that entered the Roman armoury after the Gallic Wars which bears no resemblance to anything the Romans had used before. It is the stone throwing Onager (meaning Wild Ass). Less accurate and built for throwing stones time and time again at the same place like later Medieval weapons...if there is any candidate for a pre-Roman siege weapon in Gaul, this is it. So in the end, the Gauls may have had their own shock and awe after all, and Caesar made sure no one ever heard about it - man he was good.

Wednesday 6 February 2013

The Spin Doctor

So we're starting to get a feel for what happened in 52BC. The big problem is that the only contemporary account of the year is one written by Julius Caesar himself. Imagine if all we knew about Napoleon were a few coins and a book authored by Arthur Wellesley...but that's what we're stuck with for Vercingetorix. The situation is made even worse by Caesar's understanding of spin being just as advanced as any modern politician. For example, in the Battle of Gergovia, having not slept for almost a week, Caesar makes one of the worst decisions in his life - it costs him a fifth of his fighting force in one afternoon; forces him into a full retreat; and decides for him that he must abandon Gaul entirely. Yet he manages to pass it off as 'misinterpreted orders' by his men and a minor set back (thanks to how things turned out later) - and despite tens of thousands of witnesses, he dismisses his losses as only '700' when all likelihood they were in the region of five thousand. And remember, this is a time when dispatches from central France could still reach Rome within a week...so it wasn't as though he was pulling the wool over everyone's eyes. But he wasn't writing for those who knew the truth - he wrote "The Conquest of Gaul" for the tabloid market, and he knew how to write for his public. It just goes show nothing much has changed - and when you're next reading a newspaper column or blog written by a sitting politician...ask yourself...is this really anything new?

|

| And 'A Body of Doubt' is coming very soon |

Tuesday 5 February 2013

The Druids - the last laugh?

Whether the Druids were actively pursued from the Gallic psyche, or if they were gradually usurped by new Roman administrations, one thing is fairly certain - by the end of the 1st-century AD the idea of the Druid had ceased to be - despite all of the Druid-era Gallic deities still being worshipped in one way or another. In that way we know Druids were not important to the day-to-day worshipping in Gallic temples. So maybe - more than anything - they were victims of technology? Say what? Well, an increasingly literate Gallic and British population meant fewer people were reliant on each village having a 'wise' man. There's some suggestion the influence of the Druid-caste in Celtic Gaul was already in decline by the 1st-century BC, at the same time the Gallic populous were urbanising and actively reading and writing. The degree of Gallic literacy was not underestimated by Julius Caesar - during the Gallic Wars he relied on coded missives passed through enemy lines in the fear that anything written or Greek or Latin would be recognised immediately. So was it the pen that ended the Druids? If it was, history gives the Druids one last laugh at the Romans who replaced them.

After all, what happened when the Roman Empire declined and fewer people were able to read and write? Well, they turned to village priests again, both for spiritual and intellectual guidance. One religion may have replaced another, but the tasks of a village priest in France and England returned to what they had been prior to the arrival of the Romans.

And what's more - here we are again. We all have the Internet and don't need to ask a village priest for advice again - and guess, what? We're seeing that same decline in the role of the Church in western culture. It's another example of that little paradox - 'if you wait around long enough it all happens again'. The modern day decline in western religion might actually have the same cause as the decline of Druidism 2000-years ago - when religion becomes a purely spiritual adventure rather than an intellectual one - the roles of religious leaders always seem to change, and for some that means the end to a way of life. It did then, and it might now.

Check out my latest book release - Vagabond - a runaway priestess in Gaul

Monday 4 February 2013

The Druids - a job description

So if the Druids weren't wandering about looking like Gandalf terrorising the local peasantry with the threat of an impromptu liver divination - what exactly were they doing? Well, if we are to believe anything Caesar says about them, the Druids were probably a lot like a medieval parish priest - even sharing the same belief in an immortal soul (check out Pythagorean Theorem). The way I see it, these guys would have shared very similar community roles and tasks to the Christian priests and monks that were to follow several centuries later - they were the intellectuals of the town, able to proffer insights into life and the afterlife, as well as offer advice on legal, moral and criminal matters. In the latter they may have been more hands on than their Christian successors, but then again, medieval priests weren't shy about condemning crimes against God.

So if this is what they did, why was Druidism driven to extinction? Well, most likely their fields of expertise were in competition with the Roman bureaucracies that followed the conquest of Gaul and Britain. The Romans wouldn't have been to keen on having two sets of laws in a town - or the locals seeking the Druid as an adjudicator rather than the Roman Praefect. You can see similar results after the French and Russian Revolutions where civilian courts and tribunals locked the modern Church out of civilian matters - it's very likely the circumstances post-Roman conquest were very much the same. Whether the Druids were actively sought out and persecuted as Tacitus described events in Britain - or if the Gallic Druids simply faded away into obscurity isn't easy to say, perhaps it was both - thanks to Caesar's mentioning of their habit of human sacrificing. If one thing's certain they would have been quickly removed from any roles in passing out criminal judgements and sentencing.

As for the question of them dressing like a wizard with a penchant for bedsheets? There's nothing to say they did or not. The Priestly colleges of Rome weren't afraid to don some pretty crazy costumes - so it's possible the Druids did wear religious robes...but did they do so all the time? I'd be tempted to say not. Most Roman priests (during the Republic) were drawn from civic life - they did a bit of auguring one day and the next they were back at home in their favourite tunic. I suspect the Druids followed suit. In the 1st-century BC, just like most other Gauls, they were probably clean-shaven with short hair - they may have carried or worn some symbol of office, but the lack of sightings of Druids in Caesar's 'Conquest of Gaul' does bear out the fact they looked just like everyone else.

Check out my latest book - Vagabond - a runaway priestess in Gaul

Sunday 3 February 2013

The Druids - Victims of fact or fiction?

Okay, so we've seen the Romans drew a line in the sand with the final destruction of Carthage in 146 BC - defining what they were prepared to do if a neighbouring culture was a 'little too barbaric' - such as performing human sacrifices. With Carthage gone, and with later Roman historians to be believed, that pretty much left the Gauls as public enemies number one. So, based on our modern day belief of Druid sacrifices you'd think Rome would have dealt with the question of Druidism quickly. But they didn't - Rome left the Gauls to themselves until 125 BC when the Roman Senate sent forces north to help the Massilians deal with Ligurian raiders. One thing led to another and by 121 BC the Arvernian confederation had been dragged into the conflict, resulting in an army of 180,000 Arverni and allies facing off with the six legions of Quintus Fabius Maximus. The resulting battle destroyed the Arvernian army and the following year they sued for peace, losing all of their southern territories in the process. This peace treaty still stood at the time of Caesar's Gallic conquest - and the province of Transalpine Gaul he was governing was the result of it.

The thing is, the matter of Druid barbarity was never raised during the Gallic Wars of the 2nd-century BC. Rome agreed to peaceful terms that would stand another seventy years, and the Roman Senate never pursued any claims to the complete destruction of the Arverni at the time of their greatest potential weakness. This is pretty odd considering what had happened to the presumably more culturally sophisticated citizens of Carthage. Do we know why? Well, for one thing, Greek historians writing about the Druids during the preceding century had never mentioned human sacrifices...and in fact, the first person to suggest this practice was Julius Caesar in 50 BC - a commentator we can reasonably believe had his own agenda.

So does this mean the 'barbarity' case the Romans would build against Druidism was fabricated? A-ha, you say, but what about those peat-bog bodies found across northern Europe and Britain? These are hard evidence, right? That National Geographic TV show I saw said these might have been ritual sacrifices? Well, hold on there. The Lindow Man from England is a classic case. Here's a young man who had been rendered unconscious for a period prior to his death by a blow to the head, then garrotted, his throat cut and left to die in a swampy boundary ditch. Many archaeologists have been quick to say, "Yep, this is a classic ritual sacrifice." But what's their basis for that assumption? We only believe Druids carried out sacrifices based on a claim made by Julius Caesar...if this claim didn't exist, perhaps we would have assumed something else. You see this a common problem for modern interpretations of unexplained ancient phenomena. If there's no easy answer something quickly becomes 'ritualistic'. This is bit like your toilet roll holder being dug up in 2000-years and being labelled, 'a votive offering' - this could actually happen.

All right, so if Lindow Man wasn't sacrificed, how did he end up with a garrotte around his neck in a ditch? This is where I'm going to apply some logic rather than assume the worst. Yes, someone went to a bit of trouble to kill Mr Lindow. Now, other than human sacrificing by a Druid, why would someone have wanted to make a point of killing him? Well, since the Romans had the same cultural background as the Celtics - and used garrotting for some executions, why don't we consider for a moment that Mr Lindow was a criminal the law caught up with? Not quite as exciting as a sacrifice, but a lot more likely. And at the risk of relying on one of Caesar's descriptions of Druids while discrediting another - how about this for a theory. Caesar said the Druids, "acted as judges in nearly all disputes." This probably included crimes requiring a capital punishment, an event they may have reasonably witnessed or even carried out. Could this be the origin of the human sacrifice story? More on this tomorrow.

Check out more Roman history with 'Vagabond' - available from Amazon now

Saturday 2 February 2013

The Druids - what was the problem?

History seems to mostly give the Druids a bad rap. Roman historians wrote endlessly of the hideous forest glades filled with the blood and gore of their ritual sacrifices. And if that's not bad enough, now modern culture has them dancing around Stone Henge every solstice dressed in funny clothes doing their best to impersonate a Tolkien wizard. Sadly the 19th-century revivalism and most of the Roman commentary is so wide of the mark we will probably never know what a true Druid looked like or how they acted. In truth these guys were the intellectual pinnacles of the Celtic world, they spent decades in training - studying complex mathematics, philosophy and various sciences while committing all of it to memory. By Caesar's account they paid no taxes and were exempt from military service - evidence enough of the sophisticated culture the Gauls had created prior to the Roman conquests. But is this possible evidence they weren't the blood-thirsty human auguries that history has saddled them with?

First of all, lets fix the Druids in a time and place. Druidism appears to have originated in Iron Age Britain sometime prior to the 4th-century BC and had spread into Gaul by the 3rd-century BC when Greek historians first began mentioning their 'Pythagoran' teachings. By the time Julius Caesar arrived in 58BC, the Druid class had cemented itself as the law-givers and legal adjudicators across all levels of Gallic life. Caesar himself doesn't seem to have much of an issue with them, in fact, he even befriended some, as one powerful priest (he was the Pontifex Maximus at the time) would another - which doesn't seem to suggest he thought their practices the abomination of human existence.

Okay, so what about these human sacrifices? Well, lets get into the 'Classical' mindset. You might be thinking that's hard, but essentially, the Judeo-Christian beliefs of morality that has shaped the modern world's lists of 'good and bad' originate from the Iron Are. What we think is bad, was mostly bad back then, just as what we think is acceptable now was mostly acceptable to a Greek or Roman as well. There were some exceptions, the Romans frowned on homosexuality while the Greeks didn't, but the big things like murder, rape, theft and human sacrifices were stock standard crimes. And in the case of human sacrifices, the Romans saw this as a primary motivation for attacking their neighbours if they believed it was being practiced - a slightly strange argument if we mention Gladiators - but we'll leave that alone today.

When the Romans besieged Carthage for the third time in 146BC, one of their driving ideological reasons for what was a largely an unjustified attack was to end the child sacrifices to the Punic god, Beelzebub - if that name sounds familiar that ought to show how well Roman PR worked at the time. Now considering the Carthaginians were an advanced sophisticated Classical society with similar geographic origins to the Judeans - the chances of them still carrying out child sacrifices in 146BC seem slim, and although a child necropolis has been found in the city, there hasn't been much convincing evidence the children were ritually slaughtered.

Fast forward to Caesar's conquests of Gaul between 58BC and 51BC, and the suggestion of human sacrifice occurs again. Coincidence, or was this Caesar building a case for his actions in Gaul, which at the time were largely unsanctioned and held to be illegal in Rome. Was that little bit of bad press he wrote enough to see the total destruction of the Celtic world's religious and judicial class. I guess we'll look at that tomorrow...

Check out my latest book release - Vagabond - a runaway priestess in Gaul

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)